Written by HASTS PhD students Lauren Kapsalakis and Shreeharsh Kelkar, with assistance from Rebecca Perry and Amy Johnson; photography and video by Lan Li; workshop occurred on April 26, 2013.

Session 1 of the MIT Sex Trafficking & Technology Workshop.

Session 1 of the MIT Sex Trafficking & Technology Workshop.

Speakers:

Lisa Goldblatt Grace

Mary G. Leary

Discussant:

Kim Surkan

Mitali introduces Lisa and Mary. Lisa works with vulnerable young people in a variety of capacities. She has also consulted with government on issues of trafficking and published extensively on these issues both academically and in the media. Mary was a prosecutor and has worked with a focus on family violence, sexual assault.

Kim invites the panelists to make introductory remarks. Lisa Goldblatt Grace asks, what is high-tech and low-tech in the world of trafficking and anti-trafficking? She began her work in response to the death of a young woman in Boston, co-founding a program with a variety of services that is gender specific space and sex industry survivor led, so survivor voice is loudest in the movement. She has a personal connection to this problem, as her partner is a survivor of the sex industry. Her work with My Life My Choice at JRI supports women and girls as they recover. Wherever they go, the organization will follow them with support through a survivor mentoring system that pairs each girl with a survivor mentor for one-on-one support.

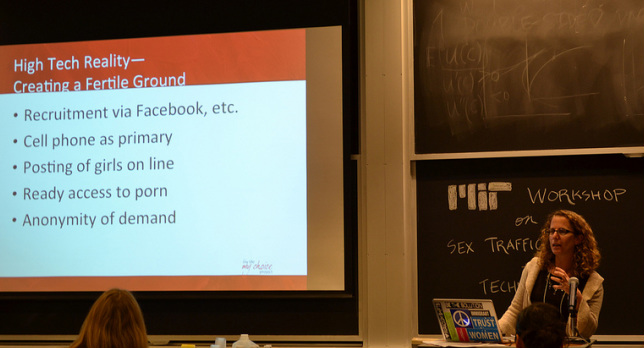

What is the high-tech reality of trafficking? It takes many forms: in recruiting (through Facebook), surveillance through cellphones, ready access to porn and the anonymity that the online world offers. Many girls get recruited into the sex industry through the internet.

While pimps continue to recruit face-to-face -- for example, hanging out at bus terminals, looking for girls who have no place to go -- there is now an additional method of recruiting: through sites like Facebook and Backpage. Almost 50% of the girls My Life My Choice has helped in the last year met the perpetrator through Facebook. Cellphones are another way of recruiting, especially considering that all adolescents usually have a cellphone. Cellphones serve as gifts, but also as a means of tracking. Technology has increased the ways that these vulnerable girls are surveilled.

This is “not our grandparents’ porn,” but a whole different way of commodifying people, particularly girls.

Lisa now offers concrete examples; these are survivors who have given her permission to use their story. Lisa shows photographs, taken by survivors, to illustrate the situation.

Maria’s experience of trafficking started when she began living with her friend and his mother The mother then forced her into prostitution, arguing that Maria needed to “pay her back.” This was a low-tech recruitment.

Laura grew up in an all-white suburb. She wound up in a group home and then became friends with an older girl, took a trip, and got recruited into prostitution in Connecticut. This was a high-tech recruitment, in which social media played a role.

Barbara’s photo portrays her as a typical teen. She wouldn't meet the full sexual exploitation definition; although her learning disability prevented her from forming relationships in real life, on Facebook she became involved in a compromising position with an older man who visited her.

Sarah was working part-time and her boss first got her addicted to heroin. A low-tech recruitment.

Lisa argues that there are certain “high-tech missteps” that we take even today. For example, we still frame concerns about online acquaintances as “stranger danger” -- be careful, there are creepy old men out there. But when we’re dealing with Facebook, the person becomes a “friend” even though you don’t know the person at all. It becomes a different social category.

She talks about an experience with teenagers; they all told her they knew not to take off with creepy old men. But the handsome young men or women who become their friends on Facebook are another story.

The second mistake is that we think we can just eliminate the technology or stop access to it. You can’t simply eliminate technology, you need to teach how to navigate it.

Finally, high-tech dangers require hi-tech responses. When girls go missing, one recovery challenge is that sometimes girls get brought back into trafficking. Facebook can be used to help find people. Status updates on Facebook, for example, like “chilling in JP” allow the organization to help find people.

Helping girls requires instrumental use of technology. We can use technology to stay connected with them, help them seek support, and even to build prosecutions. Things like social media help law enforcement target demand through online stings instead of traditional undercover methods. Technology leaves a trail.

But Lisa sees the most important piece actually as actually the low-tech. The key is to build relationships with these girls, and this is essentially a low-tech thing but it is key to ending exploitation. Service workers need to replace the same things that pimps offer -- love, community, fun -- by building a community with the girls.

Lisa Goldblatt Grace

Mary G. Leary

Discussant:

Kim Surkan

Mitali introduces Lisa and Mary. Lisa works with vulnerable young people in a variety of capacities. She has also consulted with government on issues of trafficking and published extensively on these issues both academically and in the media. Mary was a prosecutor and has worked with a focus on family violence, sexual assault.

Kim invites the panelists to make introductory remarks. Lisa Goldblatt Grace asks, what is high-tech and low-tech in the world of trafficking and anti-trafficking? She began her work in response to the death of a young woman in Boston, co-founding a program with a variety of services that is gender specific space and sex industry survivor led, so survivor voice is loudest in the movement. She has a personal connection to this problem, as her partner is a survivor of the sex industry. Her work with My Life My Choice at JRI supports women and girls as they recover. Wherever they go, the organization will follow them with support through a survivor mentoring system that pairs each girl with a survivor mentor for one-on-one support.

What is the high-tech reality of trafficking? It takes many forms: in recruiting (through Facebook), surveillance through cellphones, ready access to porn and the anonymity that the online world offers. Many girls get recruited into the sex industry through the internet.

While pimps continue to recruit face-to-face -- for example, hanging out at bus terminals, looking for girls who have no place to go -- there is now an additional method of recruiting: through sites like Facebook and Backpage. Almost 50% of the girls My Life My Choice has helped in the last year met the perpetrator through Facebook. Cellphones are another way of recruiting, especially considering that all adolescents usually have a cellphone. Cellphones serve as gifts, but also as a means of tracking. Technology has increased the ways that these vulnerable girls are surveilled.

This is “not our grandparents’ porn,” but a whole different way of commodifying people, particularly girls.

Lisa now offers concrete examples; these are survivors who have given her permission to use their story. Lisa shows photographs, taken by survivors, to illustrate the situation.

Maria’s experience of trafficking started when she began living with her friend and his mother The mother then forced her into prostitution, arguing that Maria needed to “pay her back.” This was a low-tech recruitment.

Laura grew up in an all-white suburb. She wound up in a group home and then became friends with an older girl, took a trip, and got recruited into prostitution in Connecticut. This was a high-tech recruitment, in which social media played a role.

Barbara’s photo portrays her as a typical teen. She wouldn't meet the full sexual exploitation definition; although her learning disability prevented her from forming relationships in real life, on Facebook she became involved in a compromising position with an older man who visited her.

Sarah was working part-time and her boss first got her addicted to heroin. A low-tech recruitment.

Lisa argues that there are certain “high-tech missteps” that we take even today. For example, we still frame concerns about online acquaintances as “stranger danger” -- be careful, there are creepy old men out there. But when we’re dealing with Facebook, the person becomes a “friend” even though you don’t know the person at all. It becomes a different social category.

She talks about an experience with teenagers; they all told her they knew not to take off with creepy old men. But the handsome young men or women who become their friends on Facebook are another story.

The second mistake is that we think we can just eliminate the technology or stop access to it. You can’t simply eliminate technology, you need to teach how to navigate it.

Finally, high-tech dangers require hi-tech responses. When girls go missing, one recovery challenge is that sometimes girls get brought back into trafficking. Facebook can be used to help find people. Status updates on Facebook, for example, like “chilling in JP” allow the organization to help find people.

Helping girls requires instrumental use of technology. We can use technology to stay connected with them, help them seek support, and even to build prosecutions. Things like social media help law enforcement target demand through online stings instead of traditional undercover methods. Technology leaves a trail.

But Lisa sees the most important piece actually as actually the low-tech. The key is to build relationships with these girls, and this is essentially a low-tech thing but it is key to ending exploitation. Service workers need to replace the same things that pimps offer -- love, community, fun -- by building a community with the girls.

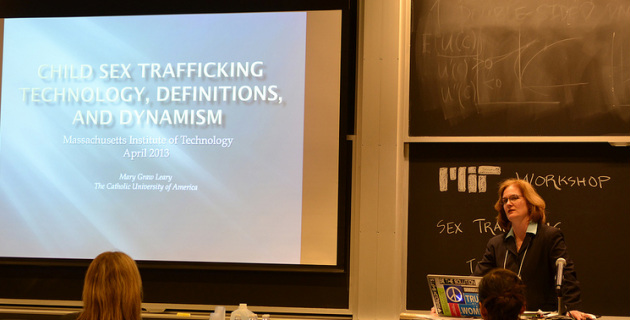

Mary Grace Leary talks today about “Child Sex Trafficking Technology, Definitions, and Dynamism”; her emphasis is on criminal law and public policy, her area of expertise.

Mary asks, what is the future of this movement? Is it going to peak? Is it going to keep moving? This is a critical period. Human trafficking causes a “broad swath of victimization.”

She, too, draws attention to language and the importance of language in this discourse.

Her work is “legal, not empirical.” She and her students have reviewed all federal child sex trafficking cases since the passage of TVPA. She suggests that studying these cases gives us an idea of the kinds of scenarios that one encounters in child-sex trafficking. Technology is complicating the scenarios of child-sex trafficking and this is something that analysts need to pay attention to. Her thesis is that defining child sex trafficking is difficult because technology is expanding its boundaries which demands a review of legal and public policy. There are statues on the books, fairly clearly written as far as statues go, but definitions remain problematic.

She draws a parallel to defining what a “terrorist” is. How you use a label is going to have implications on public policy. Language matters. In the US we use “child pornography” labels, in Europe they use “images of child abuse and exploitation”

How does the TVPA define child-sex trafficking? Sex trafficking is what is associated with “commercial sex acts.” International law stresses “exploitation” which is not related to the conventional understanding of prostitution. In Massachusetts, the focus is not on targeting prostitutes but on those who drive the industry. For children, this becomes people who “entice” them “by any means.” She asks: Is this too broad or too narrow a definition of trafficking? Does it correspond to empirical realities? She suggests that it is too broad. When she looks at the first circuit, there are only 7 child trafficking cases, but if one searches for child pornogrpahy cases, the number expands dramatically.

TVPA doesn’t require force or coercion, just that something of value is exchanged regarding a minor. This is very broad, involves enticement.

Defining child sex trafficking as when anyone entices a minor to engage in sex act where anything of value is exchanged with anyone has ramifications. She used this broad definition in her study because in criminal law sometimes things that we would normally understand as child sex trafficking will be charged under another name so that underage victims might not have to testify.

But consider this definition. Is this really what child sex trafficking is in the US? If so, that dramatically expands our notion of child sex trafficking. Federal laws are inadequate, no comprehensive laws exist in the US to address this. If you look at expanded categories of crime, the numbers of sexual exploitation and trafficking increase.

What is “something of value”? What is a “sex act”? What if a perpetrator sends out a picture of him or herself? The exchange of gifts is often important, part of “grooming” the victim, with perpetrators requesting images from victims to use later as blackmail.

She offers an example: In United States v. Davila Sanchez (1st Cir. 2006), a man was stopped at an airport with film of him assaulting a minor. The charge was child pornography but it appears to be child sex trafficking.

How has technology changed the picture? Well for one thing, enticement is now possible online.

She offers chatroom interactions as an example, perhaps dated but still being processed in the courts, with chatrooms as sites for exchange.

Craigslist has also been used to locate victims. US vs Berk is an example of craigslist used in reverse -- not for advertising services but for searching posts for recruitment opportunities. In this case, a desperate father who posted about his need for work was contacted by an offender, in hopes of luring the father into a trafficking scheme.

In US vs Lenz, a 26 year old met a 15 year old in an online game. Blizzard, the company that created World of Warcraft, had transcripts of their messages. He said he was trying to rescue her, but the messages belied that.

Mary offers some concluding remarks: It is very tempting and moral to have a broad idea of what child sex trafficking is, but we need to be careful not to dilute what human sex trafficking means in its initial definition. Overwhelmingly, the cases in court tend to focus on child pornography.

The Department of Justice reports that in numbers of cases, sexual exploitation has shifted from abuse to pornography. This means that where we saw crime before, we now see something different. But how has this played out in courts? Courts are moving away from the guidelines for pornography, moving away from the mandatory minimum sentences. By extending what child pornography means, we may have invited a backlash from the courts. She cites another scholar who asks: by concentrating on sites like Craigslist, is law enforcement missing critical opportunities? A wide definition makes absolute sense for educational purposes -- to educate parents and law enforcement -- but it may not be good for actual prosecution. It may result in us going after low-hanging fruit rather than actual instances of real exploitation.

Mary asks, what is the future of this movement? Is it going to peak? Is it going to keep moving? This is a critical period. Human trafficking causes a “broad swath of victimization.”

She, too, draws attention to language and the importance of language in this discourse.

Her work is “legal, not empirical.” She and her students have reviewed all federal child sex trafficking cases since the passage of TVPA. She suggests that studying these cases gives us an idea of the kinds of scenarios that one encounters in child-sex trafficking. Technology is complicating the scenarios of child-sex trafficking and this is something that analysts need to pay attention to. Her thesis is that defining child sex trafficking is difficult because technology is expanding its boundaries which demands a review of legal and public policy. There are statues on the books, fairly clearly written as far as statues go, but definitions remain problematic.

She draws a parallel to defining what a “terrorist” is. How you use a label is going to have implications on public policy. Language matters. In the US we use “child pornography” labels, in Europe they use “images of child abuse and exploitation”

How does the TVPA define child-sex trafficking? Sex trafficking is what is associated with “commercial sex acts.” International law stresses “exploitation” which is not related to the conventional understanding of prostitution. In Massachusetts, the focus is not on targeting prostitutes but on those who drive the industry. For children, this becomes people who “entice” them “by any means.” She asks: Is this too broad or too narrow a definition of trafficking? Does it correspond to empirical realities? She suggests that it is too broad. When she looks at the first circuit, there are only 7 child trafficking cases, but if one searches for child pornogrpahy cases, the number expands dramatically.

TVPA doesn’t require force or coercion, just that something of value is exchanged regarding a minor. This is very broad, involves enticement.

Defining child sex trafficking as when anyone entices a minor to engage in sex act where anything of value is exchanged with anyone has ramifications. She used this broad definition in her study because in criminal law sometimes things that we would normally understand as child sex trafficking will be charged under another name so that underage victims might not have to testify.

But consider this definition. Is this really what child sex trafficking is in the US? If so, that dramatically expands our notion of child sex trafficking. Federal laws are inadequate, no comprehensive laws exist in the US to address this. If you look at expanded categories of crime, the numbers of sexual exploitation and trafficking increase.

What is “something of value”? What is a “sex act”? What if a perpetrator sends out a picture of him or herself? The exchange of gifts is often important, part of “grooming” the victim, with perpetrators requesting images from victims to use later as blackmail.

She offers an example: In United States v. Davila Sanchez (1st Cir. 2006), a man was stopped at an airport with film of him assaulting a minor. The charge was child pornography but it appears to be child sex trafficking.

How has technology changed the picture? Well for one thing, enticement is now possible online.

She offers chatroom interactions as an example, perhaps dated but still being processed in the courts, with chatrooms as sites for exchange.

Craigslist has also been used to locate victims. US vs Berk is an example of craigslist used in reverse -- not for advertising services but for searching posts for recruitment opportunities. In this case, a desperate father who posted about his need for work was contacted by an offender, in hopes of luring the father into a trafficking scheme.

In US vs Lenz, a 26 year old met a 15 year old in an online game. Blizzard, the company that created World of Warcraft, had transcripts of their messages. He said he was trying to rescue her, but the messages belied that.

Mary offers some concluding remarks: It is very tempting and moral to have a broad idea of what child sex trafficking is, but we need to be careful not to dilute what human sex trafficking means in its initial definition. Overwhelmingly, the cases in court tend to focus on child pornography.

The Department of Justice reports that in numbers of cases, sexual exploitation has shifted from abuse to pornography. This means that where we saw crime before, we now see something different. But how has this played out in courts? Courts are moving away from the guidelines for pornography, moving away from the mandatory minimum sentences. By extending what child pornography means, we may have invited a backlash from the courts. She cites another scholar who asks: by concentrating on sites like Craigslist, is law enforcement missing critical opportunities? A wide definition makes absolute sense for educational purposes -- to educate parents and law enforcement -- but it may not be good for actual prosecution. It may result in us going after low-hanging fruit rather than actual instances of real exploitation.

Discussant Kim Surkan begins her remarks. She thanks the two speakers for bringing such different viewpoints to the table and suggests that questions of surveillance are also important to consider here.

The surveillance of old was done by technology that wasn’t owned by everyone; there were gatekeepers of some kind. E.g., only the police could access certain records (think: file cards, fingerprinting).

But today every single person carries this kind of recording technology in their pocket. Your phone now has functionalities for recording, geolocation, and with some apps, knowledge of where you are in relation to different people. This has shifted the picture in the debate.

This is not just relevant to the technological capabilities of victims or witnesses, but also perpetrators. Thus, for example, in the Steubenville rape case a lot of the evidence used in the trials was recorded by the perpetrators themselves.

What do you do when youth culture is so incredibly embedded in and wedded to technology?

An abolition approach will not work -- we can’t just restrict technology. How can we enlist the use of technology in the solution? Do we want to?

The Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act, designed to fight hacking and cybercrime could be expanded to include child trafficking, but that would function as a warrantless search, with law enforcement agencies able to go to Facebook, etc. to request info and get data dumps.

She leaves us with a question: What are the pros and cons of framing sex trafficking and abuse broadly and narrowly?

Q&A

Q: In all these cases of the girls, sometimes it’s technology, sometimes it’s not. Are gangs involved in sex trafficking? How do we understand statistics like the fact that 50% of cases today are girls recruited through Facebook? Is this low-hanging fruit, and in this emphasis on Facebook, might we be missing other things? Individual cases or gangs? Is the system overloaded, are we missing the big picture? Are there gangs of sophisticated pimps?

Lisa says that though gangs play a part, they are not sophisticated gangs.

Mary adds that sex trafficking is very regional. E.g., truck stops are key places for recruitment.

Lisa suggests this is exactly why low-tech response is important and the response of Truckers Against Trafficking -- who have put up “if you see something say something” type posters at truck stops -- is important.

Domestic child sex trafficking serves as an umbrella term. It includes organized crime -- the Gotti family in New York had 125 defendants in a sex-trafficking ring; charged with money laundering -- but also Crips (12 victim child prostitution ring) who met outside high school.

Is it bad to get the smaller scale crime? No, because you’re helping a victim. Guns and drugs are finite commodities, children are not.

Girls involved in larger scale crime are the ones moved more frequently.

Mary notes that her research found that child sex trafficking is highly regional; Pennsylvania research showed that trafficking happens at truck stops; 3 major highways meet in Harrisburg, PA, so traffickers are bringing victims to the location, low tech.

Q: Quantifying trafficking prosecutions is difficult. How can we use technology to get “good numbers” of human trafficking so that the numbers are credible?

Lisa says she doesn’t know. Her own organization does it in a low-tech way. They train service providers to know how to identify and respond -- file a report 51A that goes to a case coordinator and into a low-tech database, which helps them know who they are not identifying, like boys.

Mary says it’s very challenging; some are trying to use crowdsourcing on cell phones; someone in Europe is looking at cellphone images and bringing information in from that. She offers a counterintuitive point. She says that while numbers are important, they can slow us down; before acting we need numbers. While this should be a focus, she worries that we are too focused on it.

Lisa offers an example from Atlanta, a survey of street activity as a way of gathering information, numbers. Lisa explains the numbers are a moving target. Over the last 10 years, the age at which girls were referred to her has gone down, but she doesn’t think that means that in general girls are being recruited at younger numbers, referrers are just getting better at identifying cases.

She explains there is also a paradigm shift in characterizing the girls among social workers. Girls who were characterized as manipulative, promiscuous runaways are now characterized as victimized, which is sometimes why the numbers spike.

Kim suggests we need to think about what we’re trying to count -- victims, instances, what? Part of the reason we often fall back on the category of child pornography is that the digital object is easy to count. We can search for the digital object, we can manipulate the digital object, we can identify pieces of the digital object and track it all over the web.

Mary suggests that the decision to proceed on child pornography charges is partly about the cleanness or clarity of cases, an ability to get to the case. They charge child pornography in cases that are clearly child abuse because they can’t find the victim (US vs Davila Sanchez case). Over 95% of cases in the system are resolved by a guilty plea.

Lisa adds that juries are hard to convince, if the facts are “not what I expected,” jurors may find evidence difficult or hard to believe. Ideas of trafficking often revolve around “human slavery.” This is rhetoric commonly used to describe it, as existence of human slavery is hard to accept and argues for resolution. But another result is that we envision extreme images. Some victims don’t look like you expect them to look.

It’s hard to get juries to agree to things like Maria was “shackled.” Also when it’s a case of trafficking, young girls may have to give an account of sexual activity before an audience -- which is difficult and can mean loss of community. She gives an example of a victim who went through the court process and was eventually moved to a new community, but she knew nobody, had no skills, and was in despair. Those in prison had a defined sentence; the victim felt she had received a life sentence. Finally she found work for a victims’ organization.

Mary says that there was a time when prosecutors wouldn’t go forward without the victims. Now the predominant training is that you go forward without the victim. Technology can magnify trauma through technology providing more documentation -- screenshots from Craigslist, chat logs, photos -- that can further traumatize victim but also evidence is used to corroborate victims account and they don’t have to appear in court.

Q: What are examples where judges don’t give minimum mandatory sentences?

Mary explains that this sometimes occurs in child pornography cases. The reasoning of the court goes like this: ‘I have people in front of me all the time...who have committed rapes. This person speaks to not understanding the offense and just looks at pictures.’ The judge may feel that sending the person to prison violates the purpose of the guidelines, and thus not give out even minimum sentences.

There’s no lobby for child pornography possessors. But there is vocal opposition from the bench when there are so many cases that vary in so many ways -- this creates a spectrum and people start to say, this is on the lesser end of the spectrum.

Q: The NY Times had an article on how users of pornography are now made to pay. And that is a good development.

Mary mentions James Marsh from New York on mandatory sentences; there was a time when viewing child pornography was seen as victimless crime. Now that has changed. Yet the courts have not been awarding restitution. This is because it is hard to conceive of awarding damages when the victim does not not know the person who saw the media. But this is a hot issue.

Q: Proceeding from the idea that it’s a crime every time you look at an image of child pornography, it’s not illegal to look at video or images of people killing each other or bombers blowing the public up. Legally, how do these examples correspond to people looking at images of child sex?

First, Mary says this is exactly the argument the pornography industry makes. But obscene speech is not protected speech. In order to make child pornography, you have to commit a crime. And that crime is intensified and re-intensified as that image circulates. This is the rationale of the Supreme Court when it does not include child pornography in its free speech protections.

Kim adds that the circulation of images and media means that it is never “over” for the victim. And that may be one reason why child pornography is given a different status than bomb explosions on video.

The surveillance of old was done by technology that wasn’t owned by everyone; there were gatekeepers of some kind. E.g., only the police could access certain records (think: file cards, fingerprinting).

But today every single person carries this kind of recording technology in their pocket. Your phone now has functionalities for recording, geolocation, and with some apps, knowledge of where you are in relation to different people. This has shifted the picture in the debate.

This is not just relevant to the technological capabilities of victims or witnesses, but also perpetrators. Thus, for example, in the Steubenville rape case a lot of the evidence used in the trials was recorded by the perpetrators themselves.

What do you do when youth culture is so incredibly embedded in and wedded to technology?

An abolition approach will not work -- we can’t just restrict technology. How can we enlist the use of technology in the solution? Do we want to?

The Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act, designed to fight hacking and cybercrime could be expanded to include child trafficking, but that would function as a warrantless search, with law enforcement agencies able to go to Facebook, etc. to request info and get data dumps.

She leaves us with a question: What are the pros and cons of framing sex trafficking and abuse broadly and narrowly?

Q&A

Q: In all these cases of the girls, sometimes it’s technology, sometimes it’s not. Are gangs involved in sex trafficking? How do we understand statistics like the fact that 50% of cases today are girls recruited through Facebook? Is this low-hanging fruit, and in this emphasis on Facebook, might we be missing other things? Individual cases or gangs? Is the system overloaded, are we missing the big picture? Are there gangs of sophisticated pimps?

Lisa says that though gangs play a part, they are not sophisticated gangs.

Mary adds that sex trafficking is very regional. E.g., truck stops are key places for recruitment.

Lisa suggests this is exactly why low-tech response is important and the response of Truckers Against Trafficking -- who have put up “if you see something say something” type posters at truck stops -- is important.

Domestic child sex trafficking serves as an umbrella term. It includes organized crime -- the Gotti family in New York had 125 defendants in a sex-trafficking ring; charged with money laundering -- but also Crips (12 victim child prostitution ring) who met outside high school.

Is it bad to get the smaller scale crime? No, because you’re helping a victim. Guns and drugs are finite commodities, children are not.

Girls involved in larger scale crime are the ones moved more frequently.

Mary notes that her research found that child sex trafficking is highly regional; Pennsylvania research showed that trafficking happens at truck stops; 3 major highways meet in Harrisburg, PA, so traffickers are bringing victims to the location, low tech.

Q: Quantifying trafficking prosecutions is difficult. How can we use technology to get “good numbers” of human trafficking so that the numbers are credible?

Lisa says she doesn’t know. Her own organization does it in a low-tech way. They train service providers to know how to identify and respond -- file a report 51A that goes to a case coordinator and into a low-tech database, which helps them know who they are not identifying, like boys.

Mary says it’s very challenging; some are trying to use crowdsourcing on cell phones; someone in Europe is looking at cellphone images and bringing information in from that. She offers a counterintuitive point. She says that while numbers are important, they can slow us down; before acting we need numbers. While this should be a focus, she worries that we are too focused on it.

Lisa offers an example from Atlanta, a survey of street activity as a way of gathering information, numbers. Lisa explains the numbers are a moving target. Over the last 10 years, the age at which girls were referred to her has gone down, but she doesn’t think that means that in general girls are being recruited at younger numbers, referrers are just getting better at identifying cases.

She explains there is also a paradigm shift in characterizing the girls among social workers. Girls who were characterized as manipulative, promiscuous runaways are now characterized as victimized, which is sometimes why the numbers spike.

Kim suggests we need to think about what we’re trying to count -- victims, instances, what? Part of the reason we often fall back on the category of child pornography is that the digital object is easy to count. We can search for the digital object, we can manipulate the digital object, we can identify pieces of the digital object and track it all over the web.

Mary suggests that the decision to proceed on child pornography charges is partly about the cleanness or clarity of cases, an ability to get to the case. They charge child pornography in cases that are clearly child abuse because they can’t find the victim (US vs Davila Sanchez case). Over 95% of cases in the system are resolved by a guilty plea.

Lisa adds that juries are hard to convince, if the facts are “not what I expected,” jurors may find evidence difficult or hard to believe. Ideas of trafficking often revolve around “human slavery.” This is rhetoric commonly used to describe it, as existence of human slavery is hard to accept and argues for resolution. But another result is that we envision extreme images. Some victims don’t look like you expect them to look.

It’s hard to get juries to agree to things like Maria was “shackled.” Also when it’s a case of trafficking, young girls may have to give an account of sexual activity before an audience -- which is difficult and can mean loss of community. She gives an example of a victim who went through the court process and was eventually moved to a new community, but she knew nobody, had no skills, and was in despair. Those in prison had a defined sentence; the victim felt she had received a life sentence. Finally she found work for a victims’ organization.

Mary says that there was a time when prosecutors wouldn’t go forward without the victims. Now the predominant training is that you go forward without the victim. Technology can magnify trauma through technology providing more documentation -- screenshots from Craigslist, chat logs, photos -- that can further traumatize victim but also evidence is used to corroborate victims account and they don’t have to appear in court.

Q: What are examples where judges don’t give minimum mandatory sentences?

Mary explains that this sometimes occurs in child pornography cases. The reasoning of the court goes like this: ‘I have people in front of me all the time...who have committed rapes. This person speaks to not understanding the offense and just looks at pictures.’ The judge may feel that sending the person to prison violates the purpose of the guidelines, and thus not give out even minimum sentences.

There’s no lobby for child pornography possessors. But there is vocal opposition from the bench when there are so many cases that vary in so many ways -- this creates a spectrum and people start to say, this is on the lesser end of the spectrum.

Q: The NY Times had an article on how users of pornography are now made to pay. And that is a good development.

Mary mentions James Marsh from New York on mandatory sentences; there was a time when viewing child pornography was seen as victimless crime. Now that has changed. Yet the courts have not been awarding restitution. This is because it is hard to conceive of awarding damages when the victim does not not know the person who saw the media. But this is a hot issue.

Q: Proceeding from the idea that it’s a crime every time you look at an image of child pornography, it’s not illegal to look at video or images of people killing each other or bombers blowing the public up. Legally, how do these examples correspond to people looking at images of child sex?

First, Mary says this is exactly the argument the pornography industry makes. But obscene speech is not protected speech. In order to make child pornography, you have to commit a crime. And that crime is intensified and re-intensified as that image circulates. This is the rationale of the Supreme Court when it does not include child pornography in its free speech protections.

Kim adds that the circulation of images and media means that it is never “over” for the victim. And that may be one reason why child pornography is given a different status than bomb explosions on video.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed