The final session of the MIT Sex Trafficking & Technology Workshop. Video of Session 2 here and below.

Virginia Greiman (Ginny)

Abigail Judge

Discussant:

Manduhai Buyandelger

Mitali Thakor introduces Manduhai, who is teaching a class this semester on trafficking. Manduhai welcomes everyone and thanks Mitali for singlehandedly organizing this workshop. She introduces Ginny and Abigail.

Ginny Greiman describes herself as a lawyer, but not a lawyer’s lawyer. She looks at problems as business problems. How does one stop a very lucrative business? A young girl can generate $15,000 a day. How does one stop the demand?

Most of Ginny’s work has focused on international development, but her work in computer crime, cyberlaw, and international development led to interest in trafficking.

She presented on cybertrafficking at the International Conference on Information Warfare 2013, not expecting much interest. However, the room was full of men who came to the session out of curiosity about cybertrafficking. Their questions produced enough ideas to create a book.

Drawing on her work with the FBI and the Police Directorate in London, she asks, What is wrong with our investigations? Why does cybertrafficking flourish, why does it continue as a lucrative business? And how can private sector/government partner to fix this? She challenges students to develop tools to help youth stay safe. Mobile phones and other forms of technology are used to grab victims -- but “now we’re going to use technology to grab them.”

We don’t have any US statutes linking cybertrafficking with human trafficking, “They just don’t come together -- that’s amazing.” We’re not going to get there by the law alone. Law moves like a snail.

But with the use of the cloud, how do we get our hands on the evidence? There’s a tension between materials that exist in the cloud and activities on the earth that complicates this issue.

What is cybertrafficking?

Cybertrafficking is “the transport of persons by means of a computer system, internet service, mobile phone, local bulletin board service, or any device capable of electronic data storage or transmission to coerce, deceive, with or without consent for the purpose of “exploitation.”

It involves travel, movement, placement, and advertising; there are elements of exploitation, sexual and forced labor, and slavery or something similar. Recruitment or advertising is sufficient -- a victim doesn’t have to be physically moved. Transport can occur electronically, via computer system, internet server, mobile phone.

The State Department talks about using social media to recruit victims. Craigslist’s closure of adult services in 2010 generated much discussion. Law enforcement asked, how we are going to catch people with no advertising? Law enforcement follows crime wherever it goes.

There’s Backpage.com as well as many other sites you can go to. Some sites can’t be mentioned because this session is being recorded. Traffickers get on these sites and build a community. Google identifies 5,000 websites affiliated with sex trafficking.

Worldwide, reverse stings are the most common tactic used to tackle cybertrafficking. A fictional young girl will arrange a meeting with a perpetrator; law enforcement then meets the perps.

The Australian Institute of Technology says social networking sites groom children to want to participate. This behavior is happening everywhere, on all social media sites, and now even on mobile phones.

According to a Shared Hope International Report, “technology has become the single greatest facilitator of the commercial sex trade.”

Microsoft research is partnering with law enforcement efforts. Among other things, this research examines the online behavior of johns, the impact of technology on the demand for child sex trafficking, ways in which judges and law enforcement understand technology, the language of cybertrafficking, and the role of technology in improving services.

She offers some key research questions and encourages us to generate more:

- How has technology disrupted the trafficking of persons in the US?

- How has technology altered the power dynamics?

- How has the anti-trafficking network responded through the mobilization of certain actors?

- How do different constituent groups understand the role of technology in human trafficking?

Microsoft and Mark Latonero at the USC Annenberg School of Communication are studying anti-trafficking networks, asking questions like, How do different groups understand the role of technology? Are there more human trafficking victims as a result of technology or not? We don’t have good data on this.

There’s a lot of legislation; she highlights a few examples.

First, state law matters. Although these laws are of recent origin, state laws positively impact the rate at which sex trafficking victims are at least identified. Every state except for Wyoming recognizes human trafficking (but not cybertrafficking yet) as a crime. Penalties are very severe.

In Massachusetts, for example, a human trafficking conviction can yield life in prison. In Texas, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and North Dakota, perpetrators can get life imprisonment without parole. In New Jersey, human trafficking is a crime of the first degree and people can get 20 years without parole just for receiving anything of value. This could include a financier, a manager, a supervisor. This approach targets the business of human trafficking.

We also have statutes that assist tracking victims through technology. Maryland and Vermont require state departments of labor to post national human trafficking hotline info on their websites. Some states require businesses to post this as well. California, through its Supply Chain Act requires businesses to post on their websites notification of measures they have taken to eliminate human trafficking. Again, this is looking at it as a business.

Many states have child enticement statutes that draw on the use of technology in sexual exploitation. Technology is starting to be linked more and more to enticement. Alabama has a statute that looks at sexual performance on the internet; other states have similar provisions. In 2003 Texas became one of the first states to criminalize human trafficking. In MA we now have a dedicated position for dealing with trafficking.

Some states can prosecute you even when nothing happened in the state -- extrajudicial jurisdiction. Some states have statutes that allow prosecution provided some element happens within the state.

So what would a model statute look like?

First, we need to start with a definition of cybertrafficking. And remember, many of the people involved are pillars of the community. They don’t want stricter laws because they would hurt their own businesses and stature. We need rights, defenses, and protections afforded to victims. There should be no burden on the prosecutor to prove the perpetrator knew the victim was a minor. We need to think, too, about what evidence is admissible in court. We don’t want mandatory reporting, because we may be accusing people who are innocent.

She closes saying that we need to get people talking about this. We need to connect it with the internet. There are investigatory problems, problems with judges: if you do something on the internet, there’s no way to prove it involved a human being. “On the Internet no one knows you’re a dog.”

First, involvement in CSEC is not necessarily linked to mental health issues, many factors are involved. We need to look at victim vulnerability and the effects of crimes through the lens of CSEC to clarify the issues/problems.

Abigail has treated teens and children, but when she started to work with kids affected by CSEC, she realized she didn’t have a good lens with which to view these kids. She has also worked as a forensic psychologist and investigated how specific conditions are thought of and how participants differ in how they testify for the courts. They might ask, Why is this girl running away, why is she involved? But yet, the courts seldom heard testimony from a child. Although some behavior was ambiguous, when looked at through the lens of CSEC, it became clearer what was going on. Reinterpreting behavior in the light of CSEC changed the picture.

She now offers us a psychological perspective on the phenomena and examines how the effects of technology may overlay the complex phenomenon of self-disclosure. It’s important to remember that this is a system; responses from each sector affects others.

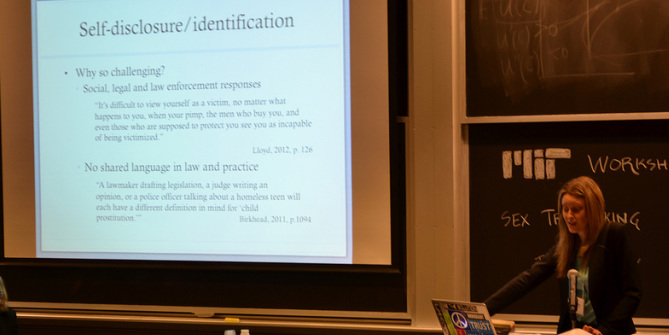

What makes self-disclosure or identification of victims such a complex process?

It’s not merely the psychological effects, there’s also a lack of shared language. Often the different sectors are working under different definitions.

Psychological adaptation to trauma results in identification with one’s exploiter, traumatic bonding and the denial of harm (Herman 1992 Farley 2013 Reid & Jones 2011).

For example, she discusses the case of decades of administrative cover up of abuse at Horace Mann and describes how deep attachment can also be involved even with exploitation, She quotes one of the victims explaining that he didn’t want to get rid of a gift given by an exploiter.

Similarly, removing tattoos made by perpetrators on victims can be complicated for victims, even adults.

She mentions Tiger Tiger, a memoir on sexual abuse. The author was an 8-year-old girl when one of her neighbors started grooming her for exploitation. The perpetrator cultivated the idea of romance to justify the crime. Some behaviors are puzzling to those unfamiliar with CSEC, these may be statements made by victims or even professional witnesses on the stand. Courts need education.

She discusses a case in Fairfax, Virginia, US v. Strom. MJ was a 17-year old female; her Facebook page described her as in a relationship with her pimp. And yet, she told investigators she did not need help, that she was living the life she chose. She recanted when interviewed; but there was a digital artifact, a Facebook page, with messages, assertion that she loves what she does. Complicated issues. What does this look like with CSEC? The CSEC view shows that many seemingly inexplicable behaviors are really adaptations to trauma.

Running away, children lose beds in group homes, makes it more complicated. She references a 2010 study by Halter, other sources including Hopper & Hidalgo, 2008; Priebe & Suhr, 2005; SHI, 2008.

How does technology affect an already complicated psychological process for victims? This is a virtually uncharted domain.

However, we know that being depicted in this way can actually inhibit kids from disclosure because it can increase feelings of complicity/guilt. When researchers in the UK asked kids why they didn’t speak out about the abuse, kids expressed a sensation that they had somehow participated in the process -- for example, because they were made to smile. There are also psychological effects when abused children are made to exploit other children or serve as recruiters.

Knowing that the past is the past and staying grounded in the present becomes very difficult when there is a recurring image.

Returning to the effects of technology on these psychological factors, technology is a double-edged sword. There may be similarities with the so-called mainstreaming of pornography, with both good and bad elements.

Research suggests that internet facilitation makes law enforcement agencies more likely to see CSEC kids as victims. Technological mediation here affects perspective and understanding of the phenomenon.

She discusses Melissa Farley’s argument that the blurring of boundaries in online spaces may be particularly pernicious; in particular, with regard to the encouragement of sexualized behaviors in girls. However, we need more research.

She finishes by saying that, given the attachment dynamics she has discussed, what Lisa noted about the effects of a transformational relationship are exactly correct. It is these relationships that we need more research about.

The language of law, for example: abducting and extortion. How can we translate this for children -- how can we educate 10-12 year old children in a language they understand? In the world of child victims, this can translate as “saving, loving, caring.” How can we help the children understand that these boundaries are permeable, that what they see as love can be abuse?

Denial, brainwashing, exploitation -- do these terms translate into a language children can understand? And how do service providers, law enforcement, legal professionals understand them?

A 15-year old describing her abuse may seem detached. Her tone may confuse law officials; as a result she may not receive sympathy or understanding.

How do the police understand the language of the child, of the medical professional? How do they get into the same world? These groups speak different languages. The sociocultural aspects of language are important as well. There can be stigma and baggage attached based on cultural values, gender values, etc.

Manduhai reminds us that technology is a double-edged sword. Technology is nothing until someone uses it. Facebook is a tool. YouTube acquires different meanings depending on how it is used.

There’s a need to stop thinking of trafficking as occurring only between perpetrators and victims, to look into the impact of the business more broadly, to look into the people who are connected to the system but are unaware or in denial of their connections. There’s a need to increase penalties and decrease funding sources.

Technology is both tangible and not -- we need to widen and abstract the definition of technology. As we do, technology becomes an important center, revealing the agents behind it.

Q&A

Abigail says that we need to empower girls to recognize recruitment when it happens. It’s very complicated.

Manduhai adds that community building is also an important part of the solution.

Ginny explains that she’s working with the FBI to educate very young children. Language is part of the problem -- as an anthropologist Manduhai articulated it. We could use more ways of getting us to talk the same language, use the same terms.

Q. With regard to Virginia’’s remarks on the business model, I worked as psychotherapist with people with multiple personalities. There’s an economist studying internationalization after the fall of the Soviet Union, who examines money laundering and the oligarchs who are appropriating the wealth of the former communist countries. These are highways where trafficking occurs. I still have a question about the missing language, the voice missing from our conversation. Is there some integrated way of looking at these issues?

Ginny explains that there isn’t really anything out there. The US State Department has some numbers, and the UN has offered some statistics through UNICEF, but there’s no government structure to address this.

Sarbanes-Oxley required CEOs to be accountable for financial information they were putting out--this was a change in financial regulation. There’s no comparable structure for trafficking reporting. We haven’t come together uniformly like we have for other crimes -- for example, drug trafficking. We don’t agree, we have different privacy laws. This is a difficult hurdle. People need to come together, start to focus on it.

Abigail adds that there has to be a community-based or collective element, too.

An audience member recommends a book called Pornland by Gail Dines, which discusses the effects on boys of seeing porn on the internet. Research shows some of these boys thought women enjoyed prostitution.

Manduhai says it is important to improve communication; tracking, reaching out... But we should also talk about technology in general -- the technology that produces images, not just the technology that produces relationships. The media perhaps doesn’t want to engage with this. Rather, it often glorifies anything related to sex and prostitution. Media representations often portray prostitutes as beautiful women, with appealing lifestyles. This affects young children’s understanding.

Abigail references the controversy a while ago about a how-to-be-a-pedophile book on Amazon (probably The Pedophile’s Guide to Love and Pleasure); and yet, on Amazon there are many books on pimpology and how to recruit girls.

Ginny argues that we need more examination on what is allowing this to flourish. It is a flourishing industry.

Mitali ends session 2 there, thanking everyone.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed